This post was originally published on this site

https://www.gannett-cdn.com/presto/2018/07/31/PLOU/e4426df6-4d8f-449a-ae1e-4bc30396242f-civil_rights-busing02_photo.JPGLouisville wouldn’t be what it is today without Black people who established some of the city’s most historic neighborhoods, fought for equal rights alongside prominent national figures and contributed to the community’s deep-rooted culture.

Below are six stories of people and moments that shaped Louisville’s history.

To explore more, visit the University of Louisville Oral History Center, the Filson Historical Society, Roots 101 African-American Museum, the Kentucky Center for African American Heritage and the Muhammad Ali Center.

More:Celebrate Black History Month by looking back on Kentucky history makers

Two enslaved Black men present at Louisville’s founding

Cato Watts, a fiddler, and Caesar, a carpenter, were two enslaved men brought to Louisville by early settlers in the 1770s, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville.

By 1810, enslaved African Americans made up 36% of the city’s population, according to University of Louisville research. And by the 1840s, domestic slave trading thrived along the Ohio River, with slave pens located in the old downtown area of the city.

After the Civil War, freed Black residents established several communities that remain an important piece of Louisville’s fabric today, including Smoketown, Limerick, Petersburg and Berrytown.

Read more:

More:The traffic signal and corded bed: 8 Black inventors you didn’t know were from Kentucky

Black jockey rides first Kentucky Derby winner across finish line

In 1875, Oliver Lewis, a Black man born into slavery, rode Aristides to victory in what would become known as the Kentucky Derby.

Lewis is one of several prominent Black jockeys who participated in the early years of the race. (Of the first 28 winning jockeys in the Derby, 15 were Black.)

But by the early 1900s, those same Black equestrians were forced out of racing by Jim Crow laws that enforced segregation. More than 100 years later, Black jockeys remain a rarity in the sport.

Read more:

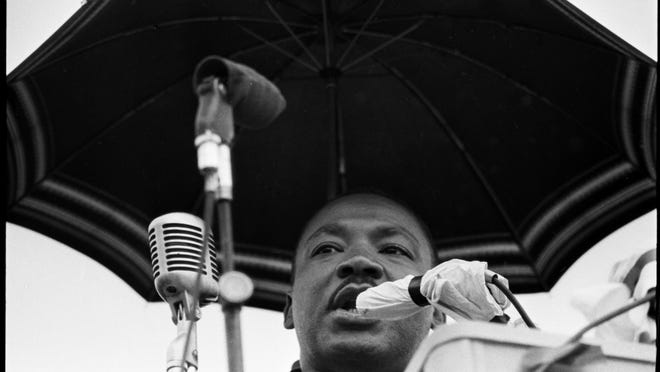

Martin Luther King Jr. part of local civil rights fight

In the 1950s and ’60s, Martin Luther King Jr. visited Louisville several times to encourage voting and advocate for policies that would end segregation.

In 1964, he and Jackie Robinson led a march of 10,000 people to the state Capitol in Frankfort, following the 1963 March on Washington.

In 1965, his brother, A.D. Williams King, moved to Louisville as a minister at Zion Baptist Church. And in 1967, the siblings led protests against unfair housing practices that culminated in a boycott of the Kentucky Derby.

That same year, King met Louisville native Muhammad Ali publicly for the first and only time. Though both men were influential in fighting human rights battles, they disagreed on some key issues and had a complex relationship.

Read more:

More:The first time I met Martin Luther King Jr., I knew I could follow him anywhere

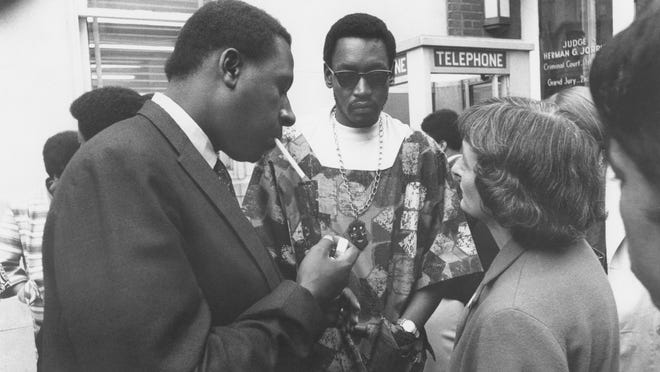

High school students help force integration at Louisville businesses

In 1961, Black students from Central and Male high schools organized months of pickets and sit-ins at downtown businesses that refused to let them eat, try on clothes or watch moves alongside white customers.

The teens’ actions led nearly 200 businesses to integrate within six months. And in 1963, the city’s mayor signed an ordinance granting equal access to all public accommodations — a year before federal protections were put in place.

“It was pretty exciting, that’s the way I remember it,” said Beverly Neal Watkins, who participated in the protests. “You felt like you were doing something good.”

‘Black Six’ put on trial for 1968 rebellion

In 1968, Louisville officials accused six Black people of orchestrating a racial uprising in the Parkland neighborhood, during which dozens of businesses were burglarized and set aflame.

The defendants — known as the Black Six — each were charged with conspiring to destroy private and public property. And for two years, their lives were in limbo as they awaited trial.

In summer 1970, a judge threw the case out of court. But by then, it had already left a permanent mark on Louisville’s history, a reminder of the ways the city repeatedly fought to quiet Black dissent.

Read more:

Breonna Taylor protests draw international outrage

In March 2020, Louisville police officers fatally shot Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman, while serving a “no-knock” search warrant at her apartment as part of a narcotics investigation.

After audio of a 911 call made by Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, on the night of her death was released, thousands took to Louisville’s streets in protest, demanding officers involved in the shooting be fired and arrested.

Daily marches and demonstrations continued for more than four months, with protesters using Jefferson Square Park downtown as a home base.

Protesters globally invoked Taylor’s name, along with George Floyd’s, while marching in other cities through the summer. And in Louisville, demonstrators added two more names to their chants after restaurant owner David McAtee and photographer Tyler Gerth were killed.

Read more:

Still want to dive deeper? Here are more stories and videos to bookmark:

Hayes Gardner and Savannah Eadens contributed to this report.

Reach reporter Bailey Loosemore at [email protected], 502-582-4646 or on Twitter @bloosemore. Support strong local journalism by subscribing today: https://www.courier-journal.com/baileyl.