With their trademark Hawaiian shirts, tactical gear, and AR-style rifles, the Boogaloo Bois burst onto the American protest scene in 2020, testing the limits of open-carry laws while rallying around shared fantasies of armed insurrection. At the center of their movement was Mike Dunn, then a 19-year-old baby-faced former Marine, who’d built a name for himself organizing militia groups across Virginia.

But it wasn’t just flashy displays of defiance and edgy memes that made the Boogaloo Bois infamous: That year, Boogaloo members racked up charges for shooting at police stations, plotting to sabotage the power grid, participating in a conspiracy to kidnap the governor of Michigan, and even attempting to sell arms to Hamas.

But the breaking point for the government was when a Boogaloo Boi murdered two law enforcement officers in California. The DOJ formed a task force to investigate anti-government extremists and the FBI began knocking on doors. Six months later, almost as quickly as these floral-shirted militants had materialized on American streets, the Boogaloo Bois disappeared from public view. Even Dunn hung up his Hawaiian shirt, changed his phone number, got a job at a county jail, and laid low for a while.

The sudden disappearance of the Boogaloos fueled speculation that the slew of DOJ investigations and arrests had literally taken them off the board—perhaps destroying the movement forever. “The fact of the matter is the FBI won,” a once-prominent Boogaloo from Texas recently wrote online.

While it’s true that the threat of prosecution caused the Boogaloo Bois to lower their profile, the fierce anti-government ideology underpinning the movement never went anywhere. And now, the Boogaloo Bois appear to be regrouping, plotting their public comeback to coincide with what many fear could be a tense, even violent, presidential election season.

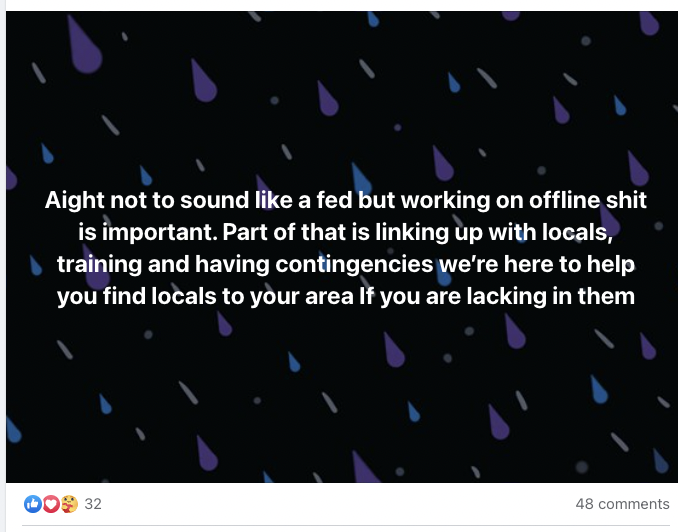

In the last six months, the Boogaloo Bois have returned to Facebook and are using the platform to funnel new recruits (and “OG Bois”) into smaller subgroups, with the goal of coordinating offline meet-ups and training, according to data obtained by the Tech Transparency Project and shared exclusively with VICE News. They’re posting propaganda videos, guides to sniper training and guerilla warfare, and how-tos for assembling untraceable ghost guns. “The Bois are back in town,” declared a member of one of the new groups. (Facebook deleted many of the groups after VICE News reached out for this story.)

Dunn, now 22 and recently returned from fighting Russia as a volunteer soldier for Ukraine, once again calls himself a Boogaloo Boi and is consumed by fantasies of becoming a martyr on the streets at the hands of the U.S. government by refusing to comply with police orders and fighting back. He says he’s 100 percent in support of an “armed revolt.”

“We all die there in the street, at the hands of the National Guard or whatever. That would spark a revolution in the state of Virginia, which would spill over into other states,” Dunn told VICE News recently. “I don’t see it as a lone wolf act of somebody blowing up a building or an attack on anything, but as a defense of liberty, creating martyrs in the name of the Constitution and freedom.”

Dunn claims he’s training with a group of more than 100 Boogaloos in Virginia that calls itself “Sons of Liberty” and threatens to go to battle if Virginia tries to pass gun safety legislation. “We will go to war,” said Dunn. “We will fight, we will die, and we will kill.”

The perfect storm for an anti-government movement

Since about 2015, extremely online gun enthusiasts have used “Boogaloo”—drawn from the title of the 1984 breakdancing film Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo—as a meme to signal a coming civil war or uprising.

This fantasy formed the basis of a community that started on 4chan’s /k/ weapon’s board and later moved to Facebook, where it continued to grow, drawing in an array of shitposters, preppers, hardline libertarians, militia dudes, gun dudes, Trump supporters, plus some neo-Nazis and white nationalists.

At the outset of 2020, it was a free-for-all for the Boogaloo on Facebook, where they developed a shared language of memes, often coding violent rhetoric or threats with layers of irony. There, they came up with homonyms for Boogaloo to skirt early moderation efforts; “Blue Igloo” or “Big Luau” were popular examples, and inspired the Hawaiian shirt aesthetic as well as the images of igloos that they feature on their flag.

Anything about Boogaloo Bois or anti-government groups we should know about? Send email tips to [email protected] or on wire @tesstess.

The first sign that the online community was morphing into a real-life movement was in January 2020, at an annual gun rally in Richmond, Virginia. Amid the thousands of grizzled gun owners who’d come to the Capitol to protest pending gun bills that day, were a group of young, heavily armed men. Their gear was decorated with colorful patches, including one featuring Pepe the Frog (the cartoon character co-opted by 4chan and the “alt-right”), with the words “Boogaloo Boys.” Another held a sign saying “I Dream of a Boogaloo.”

Anger over COVID-19 lockdowns opened the floodgates for anti-government sentiment, creating ripe conditions for the Boogaloo Bois’ ideology. After George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 sparked a national racial justice movement, the Boogaloo Bois saw an opportunity to advance their goals of societal unrest.

Boogaloo Bois and their Hawaiian shirts suddenly became mainstays of American protests across the political spectrum. And on Facebook, they were able to reach, radicalize, and recruit “normies” into their ranks.

It wasn’t until Steven Carrillo, a Boogaloo Boi and Air Force staff sergeant, shot and killed a federal security officer and a sheriff’s deputy in California, that Facebook took action against the Boogaloo movement. In late June 2020, they banned the Boogaloo movement, declaring it a “dangerous network” for “actively promoting violence against civilians, law enforcement and government officials and institutions.”

Carrillo, who is currently serving a 41-year prison sentence, encountered the Boogaloo movement on Facebook during a particularly difficult time in his life. He’d recently returned from a deployment in Kuwait, lost his wife to suicide, and attempted to take his own life several times, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, which charted how he was radicalized into the movement. (Last year, the sister of the murdered federal security officer filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Facebook’s parent company Meta, seeking to hold it liable for her brother’s death. VICE News asked Meta about the status of the case. “We work closely with experts to address the broader issue of internet radicalization,” a Meta spokesperson said. “These claims are without legal basis.”)

“I was frustrated in 2020, because I knew these guys were dangerous, I knew this was happening, I saw regular people getting radicalized in these groups, and I saw the algorithms pushing people towards the Boogaloo,” said Katie Paul, director of the Tech Transparency Project, a big tech watchdog that’s been tracking the Boogaloo on Facebook since it emerged. “Now, once again, we’re seeing the same ramp up. We’re seeing current and former military engaging in these groups. And the calls for violence are even more explicit than they were.”

One anti-government meme group, “Sounds like Something the ATF Would Say,” has recently been flooded with explicit Boogaloo content, and now has over 100,000 followers. The Tech Transparency Project found that the group had gained over 2,000 followers in the last few weeks alone.

Boogaloo Bois were using that group to siphon off users into smaller groups (at times even using QR codes to redirect them). Those groups easily skirted Facebook bans by simply misspelling well-known terms associated with their movement. The fact they were able to do that is an example of what Paul claims is “shitty moderation.”

But a spokesperson for Meta told VICE News that they’re operating in an “adversarial space, where perpetrators constantly try to find new ways around our policies, which is why we keep investing heavily in people, technology, research and partnerships to stay ahead of them to help keep people safe from extremist activity.”

“The water is not boiling but the flame is on”

Boogaloos have also been circulating a newly redrawn “manifesto,” a sign that the once-sprawling (and often hard-to-pin-down) movement is honing and narrowing its ideology.

“If it is radical and extreme to simply want to be left alone, then we will be radical, and we will be extremists,” the 22-page document states. “One does not shake the hornets’ nest and complain of the venom.”

“The difference between now and 2020 is they have their ideology figured out,” said Paul. “I’m extremely concerned because with these new Boog groups, there’s no longer any effort to appear to be careful in terms of what they’re posting. They’re going straight to the ‘kill tyrants.’ ‘kill congresspeople’ memes.”

They’re plotting their return at a moment when anti-FBI sentiment has surged in mainstream discourse, thanks in part to the baseless “Fedsurrection” conspiracy claiming federal agents orchestrated the Capitol riot to smear Trump supporters.

“The difference between now and 2020 is they have their ideology figured out”

The biggest impetus for the Boogaloo’s recent return to Facebook, says Paul, was the FBI’s raid on former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-lago property last August. That raid triggered a wave of violent threats from MAGA-world and calls for civil war. Days after the raid, a Trump supporter with a nail gun attempted to storm into the FBI’s office in Cincinnati (he was later killed following a police standoff in a nearby cornfield).

One member of a Boogaloo Facebook group responded to the news, posting an image of a nail gun.

Even as the Boogaloo movement retreated to the shadows in recent years, its trappings lingered. The online firearms marketplace guns.com now sell their own Hawaiian shirt, emblazoned with their company logo. FenixAmmo sells a “Big Luau Competition Jersey” in Hawaiian print, as well as stickers with the Boogaloo flag (featuring a stripe of Hawaiian print, and an igloo in the top left corner). One person is even selling a “Blood of Tyrants” wine.

Given the growing normalization of anti-government rhetoric, experts fear that it wouldn’t take much for the Boogaloo Bois to return to the streets.

“The water is not boiling but the flame is on, and the water is still hot,” said Jon Lewis, research fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. “It won’t take much to get to that point again like we saw in 2020, where there is sufficient cause to mobilize.”

Paranoia, paranoia

According to the GWU’s Program on Extremism, there were 49 arrests of people affiliated with the Boogaloo movement from 16 states between January 2020 and July 2022. A trickle of Boogaloo arrests continue to the present day.

In January, an active-duty U.S. marine who expressed support for the Boogaloo movement online was arrested for his alleged role in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. Last month, federal law enforcement seized 11 guns, a silencer, body armor, more than 1,000 rounds of ammo, and several pounds of explosive material from Timothy Zegar, an alleged Boogaloo Boi from Springfield, Missouri. Federal prosecutors say he was “trafficking” firearms, despite having a prior felony conviction from a 2014 high-speed chase.

In court documents, prosecutors noted that in 2020 Zegar posted in a Facebook group that the “end game is capturing the senate and house and publicly executing them” and said he was willing to be “a martyr for the cause.”

The FBI will tell you that they do not, under any circumstances, investigate an ideology. “The FBI can never open an investigation based solely on protected First Amendment activity,” a spokesperson for the Bureau told VICE News. “We cannot and do not investigate ideology.”

But Zegar’s arrest is a pretty good example of federal law enforcement’s approach to the Boogaloo movement, often arresting people they might be particularly concerned about on relatively low-level federal offenses, like gun violations or interstate threats.

It’s a strategy that many in the movement are all too aware of. “I know the feds watch my show,” Boogaloo-adjacent podcaster Joshua Smith said during a broadcast of his show in November. “Trust me when I say that the federal government wants to make an example of any ‘Boi’ they can find and pick up for any reason. If they could get you on a fucking driving offense, they’re gonna find a way to put you in jail.”

It’s not exactly paranoia. At least 52 percent of Boogaloo arrests in George Washington University’s tracker were the result of an operation involving an informant or undercover agent. By the end of 2020, Boogaloo chats were rife with finger pointing, with many accusing one another of being a “fed.”

Dunn, in particular, faced a barrage of accusations that he was a “fed” or cooperating with the government, which he adamantly denies. Boogaloo Bois continue to accuse one another of working with the federal government, but such accusations are now so commonplace that they’ve almost become a meme in themselves. (The paranoia about federal infiltration exacerbated infighting between various cells, which had partly stemmed from the vague political orientation of the Boogaloo Bois—some chapters aligned themselves with leftist anarchists, others welcomed neo-Nazis into the fold.)

Leaving the Boogaloo Bois

For some Boogaloo Bois, the mere threat of federal investigation was enough of a reality check to get them to cut ties with the movement.

That was the case for Blake from Oklahoma, who was just 18 when he became a Boogaloo Boi in 2020. (Blake has asked that we withhold his last name, as he is trying to move on with his life after leaving the movement).

“I didn’t really have any friends. I was just some loner high school kid that had nothing going for him,” said Blake. “So, I joined an extremist group, if you will.”

His involvement in the movement never escalated to real-world meet-ups, but he makes no bones about the fact that, over time, he became enmeshed with some dangerous people online. “You had guys coming in, saying that they wanted to blow stuff up or shoot people,” said Blake, recalling his time in some Boogaloo-adjacent Telegram channels.

“I left the group because I didn’t want to go to jail. In fact, I was investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and I was told, it’s either leave, or continue down the path and get yourself in trouble,”claimed Blake. “I was just a kid at the time.”

“The best way I can describe the movement as I see it nowadays is a terrorist organization that doesn’t commit acts of terror,” he added.

And while getting a visit from the FBI might have been enough to scare off some Boogaloo Bois, others are unfazed by the prospect of federal surveillance. “Always expect the feds to know what you’re going to do and just embrace it, accept it, and learn to plan on the fly,” said Dunn. “As long as we keep our nose clean and don’t plan illegal things beforehand, there’s no way for the feds to prevent it.”

This marks a concerning shift for those on the outside watching the Boogaloo movement evolve.

“A lot of people aren’t afraid of the federal government or the FBI anymore,” said Blake. “There are people out there that I knew personally, that openly talked about slaughtering federal agents, like dragging them and politicians into the streets and killing them. They have no fear. They don’t care.”

“You can’t prosecute your way out of a narrative”

Boogaloo Bois like Blake, who joined the movement for a sense of belonging rather than deep ideological affiliation, might have been low-hanging fruit for the FBI.

But others who harbored genuine animus towards the federal government pose a bigger challenge.

John Subleski and Addam Turner, both from Louisville, Kentucky, were prominent figures in a local Boogaloo cell called the Pharaoh National Guard—until they wound up in prison in 2021. Subleski was arrested for using social media to incite a riot, and Turner for using social media to make interstate threats.

They’re both currently on supervised release, and have agreed to stay off social media for the time being. “I’m not allowed on any of those [platforms] anymore, because that’s part of my agreement, the government doesn’t want me telling people what happened on the internet or rallying the troops,” Subleski said. “I’m biding my time until I can get back online and cyberbully the government I guess.”

And although neither Subleski nor Turner expressed a desire to eventually rejoin the movement, they did say that their experience in the criminal justice system only affirmed the anti-government ideology that led them to the Boogaloo movement in the first place.

Subleski, who came to the movement with years of experience in the anti-government and militia movement under his belt, had been familiar with the Boogaloo meme since its inception online, around 2015. Louisville emerged as a particularly intense flashpoint for the racial justice protests of summer 2020, because of localized anger over the police killing Breonna Taylor, a Black medical worker and resident, in a botched no-knock raid.

Subleski and others in the Pharaoh National Guard would go out to protests dressed for war, equipped with guns, zip ties, smoke grenades, flash bangs, a flare gun, and a drone camera. He got his first visit from the FBI that September. He said at first, it seemed like the feds just wanted to “build rapport.” From that initial visit, Subleski’s Facebook posts grew increasingly unhinged—later cataloged in a federal complaint.

Subleski’s biggest regrets from his time in the Boogaloo is trusting people in the movement who he believes ultimately betrayed him by talking to the feds (seven members of the Pharaoh National Guard were taken into federal custody for questioning, but only he and Turner wound up facing charges).

“I regret allowing some people to get as close to myself and others as I did, for it to fall apart the way it did,” Subleski said. Turner’s biggest regret was how public he was about his affiliation in the movement online.

“I don’t regret getting involved,” said Turner. “Did I learn things and would I do it differently next time? Absolutely.”

Both Subleski and Turner believe that they were only arrested because the government wanted to silence them, and that, in many ways, they were “proved right.”

Asked whether Subleski could still relate to the person he was when he joined the Boogaloo in 2020, he said he wasn’t sure.

“I think he’s in there, I think. I don’t know if I can say that I still relate to that person or not, but I know that person’s in me,” Subleski said. “I think that person is in all people, and I think it’s just a matter of what it would take to wake that up inside of somebody.”

The return of the Boogaloo movement despite aggressive law enforcement action over recent years is a salient reminder that the criminal justice system isn’t really a panacea for ideological problems. “That’s always going to be the challenge here,” said Lewis from George Washington University. “You can’t prosecute your way out of a narrative.”

And what’s more: FBI infiltration and arrests seems to have made some in the movement even angrier towards the government.

“The people that were arrested, the people that were charged, they just made us more angry, they made us more hateful towards the government,” said Dunn. “That hatred for the U.S. government is just sitting there. We’re thinking. We’re learning to be smart.”

Follow Tess Owen on Twitter.